On November 22, 1963 Chattanooga had three TV stations, each with only a handful of news reporters. There were about a dozen radio stations, mostly on the AM band, all live and local. The city had two daily newspapers. In the twenty-two years since the attack on Pearl Harbor, there had been no “earth-shattering” moments that stopped the presses or interrupted the flow of game shows and hit records. Then came that fateful Friday at 1:40 p.m. Eastern time.

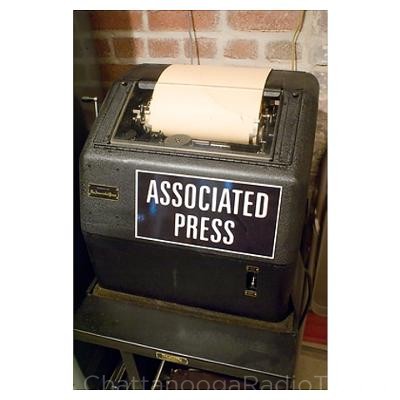

WFLI, at 1070 on the AM dial, was “where the big hits roll,” according to the promos. Lesley Gore, Dion and Roy Orbison were on Tommy Jett’s playlist that afternoon, along with the allegedly naughty “Louie Louie” by the Kingsmen. Nobody understood what the lead singer was saying, but we all figured he was up to no good. “TJ the DJ” was looking for his next record when the white light started flashing, the one connected to the AP wire machine. The clackety-clack teletype printing went on day and night in the closet-sized room behind the disc jockey’s chair. Every hour or so, he would rip a few stories off the wire and condense them into a brief newscast, headlines only. That white light would flash now and then, signaling a bulletin, but it was rarely enough to stop the music. A business fire in Chicago, a new Prime Minister in Great Britain. Big stories for sure, but not on a teen-oriented music station. On this Friday afternoon, Tommy was finally bothered enough by the flashing light to start to check the wire machine. About that time, the “hotline” rang, the phone number known only to WFLI’s management. Chief Engineer Joe Poteet had heard the first reports from Dallas. “The president’s been shot,” he told Tommy. “I turned white as a sheet,” Tommy said. “I was 23 years old and I didn’t know what to do. We didn’t have a national radio network, we were all local. I tried to keep going, and read the wire copy, but I was really having trouble.”

WFLI, at 1070 on the AM dial, was “where the big hits roll,” according to the promos. Lesley Gore, Dion and Roy Orbison were on Tommy Jett’s playlist that afternoon, along with the allegedly naughty “Louie Louie” by the Kingsmen. Nobody understood what the lead singer was saying, but we all figured he was up to no good. “TJ the DJ” was looking for his next record when the white light started flashing, the one connected to the AP wire machine. The clackety-clack teletype printing went on day and night in the closet-sized room behind the disc jockey’s chair. Every hour or so, he would rip a few stories off the wire and condense them into a brief newscast, headlines only. That white light would flash now and then, signaling a bulletin, but it was rarely enough to stop the music. A business fire in Chicago, a new Prime Minister in Great Britain. Big stories for sure, but not on a teen-oriented music station. On this Friday afternoon, Tommy was finally bothered enough by the flashing light to start to check the wire machine. About that time, the “hotline” rang, the phone number known only to WFLI’s management. Chief Engineer Joe Poteet had heard the first reports from Dallas. “The president’s been shot,” he told Tommy. “I turned white as a sheet,” Tommy said. “I was 23 years old and I didn’t know what to do. We didn’t have a national radio network, we were all local. I tried to keep going, and read the wire copy, but I was really having trouble.”

Another engineer who doubled as a deejay, Ed Aslinger (known as Ed Gale) stepped in and calmly kept listeners informed. “Thank God for Ed,” Tommy said. “I was too torn up, I was just shocked.”

Ed Aslinger remembers: “I had taken the day off – Sandy and I – we had married in June – were moving to a new apartment, and had stopped at her Mom’s for lunch. She was watching soaps on CBS. As soon as I saw the report I left for the station. Tommy and the office staff were in something of a panic. When I got there I started pulling AP wire copy. (Station manager) Johnny Eagle asked me to read the news, which I did for a very long time. Someone said six hours or more. Seemed a nightmare as I read, the awful truth sinking in as more and more flowed through me, from the wire to the listeners. The next day, they gave Sandy and I a silver tea service. Later Sandy said “This is nice of them.” I cried.”

As the long day continued, WFLI put aside the rock ‘n roll, switching to religious music as the city mourned.

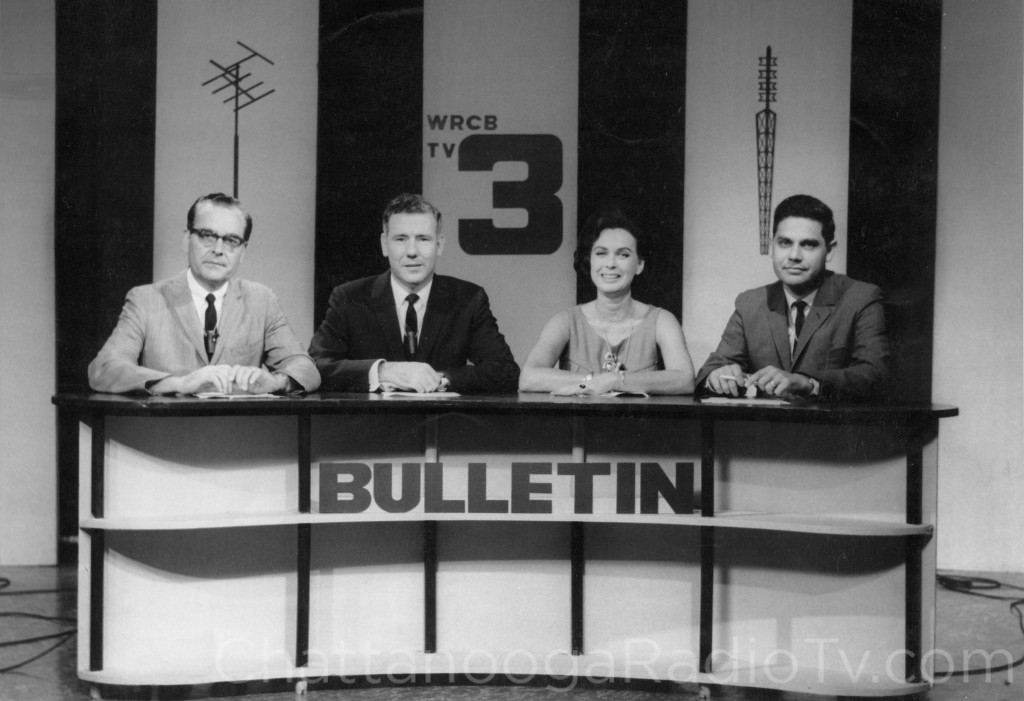

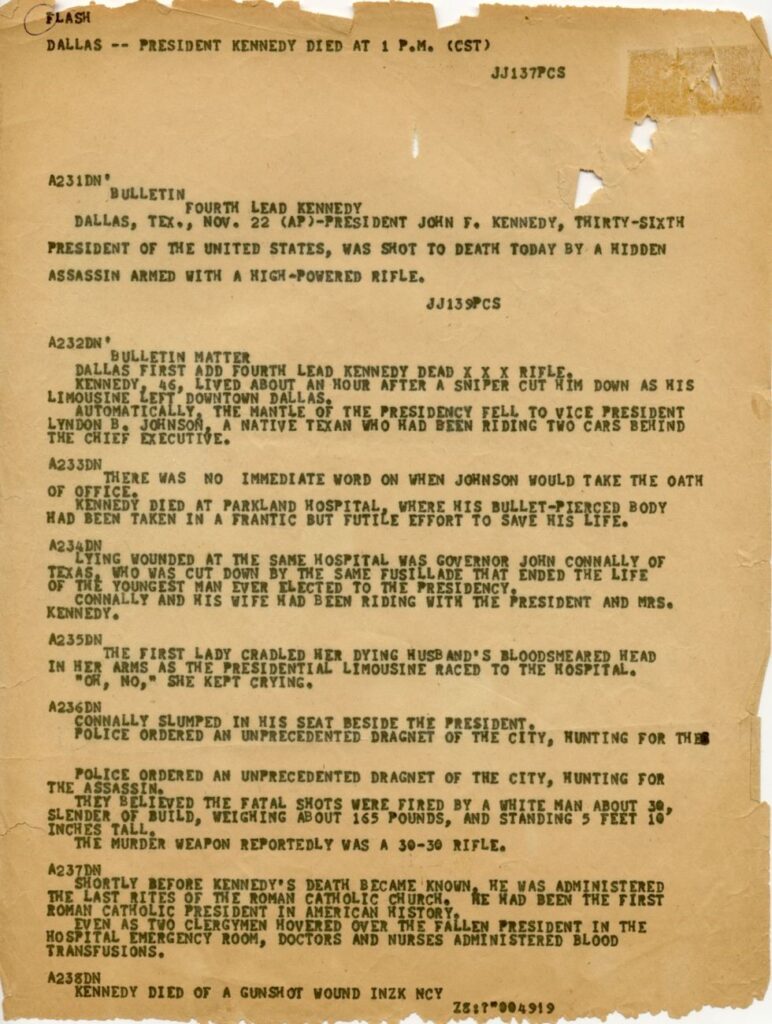

At Channel 3’s studio on McCallie Avenue, a local program called “Bulletin” was on the air. (Channel 9 was airing its daily “One O’Clock Movie,” and Channel 12 was showing the CBS soap opera “As The World Turns” until the newsroom went live. From 1:30 until 2:00 each afternoon, NBC allowed its affiliates to program their own local shows. Roy Morris (above, second from left) hosted the daily “Bulletin,” joined by fellow staffers John Gray, Joan Barry and Don Fischer. The quartet would discuss local topics, with Ms. Barry offering a rare woman’s view in the days of male-dominated TV. Producer Wayne Abercrombie can’t recall exactly what the conversation was about on this day, but he remembers hearing five bells sound off on the AP machine across from the control room. It wasn’t unusual to hear one or two bells, but five? That was a first. He made the short walk to the newsroom, and couldn’t believe his eyes. “I had to look twice,” he said. “I walked into the studio while they were in the middle of talking, and just handed the copy to Roy. He looked at it, then looked at me and said ‘Is this for real?’ This was on live TV. I shook my head and said yes. That’s how we broke the news.”

At Channel 3’s studio on McCallie Avenue, a local program called “Bulletin” was on the air. (Channel 9 was airing its daily “One O’Clock Movie,” and Channel 12 was showing the CBS soap opera “As The World Turns” until the newsroom went live. From 1:30 until 2:00 each afternoon, NBC allowed its affiliates to program their own local shows. Roy Morris (above, second from left) hosted the daily “Bulletin,” joined by fellow staffers John Gray, Joan Barry and Don Fischer. The quartet would discuss local topics, with Ms. Barry offering a rare woman’s view in the days of male-dominated TV. Producer Wayne Abercrombie can’t recall exactly what the conversation was about on this day, but he remembers hearing five bells sound off on the AP machine across from the control room. It wasn’t unusual to hear one or two bells, but five? That was a first. He made the short walk to the newsroom, and couldn’t believe his eyes. “I had to look twice,” he said. “I walked into the studio while they were in the middle of talking, and just handed the copy to Roy. He looked at it, then looked at me and said ‘Is this for real?’ This was on live TV. I shook my head and said yes. That’s how we broke the news.”

By 2:00 p.m. NBC took over the airwaves with near-nonstop coverage that would span four days. There would be no local news on Channel 3, or other TV stations until after the President was buried on Monday, November 25.

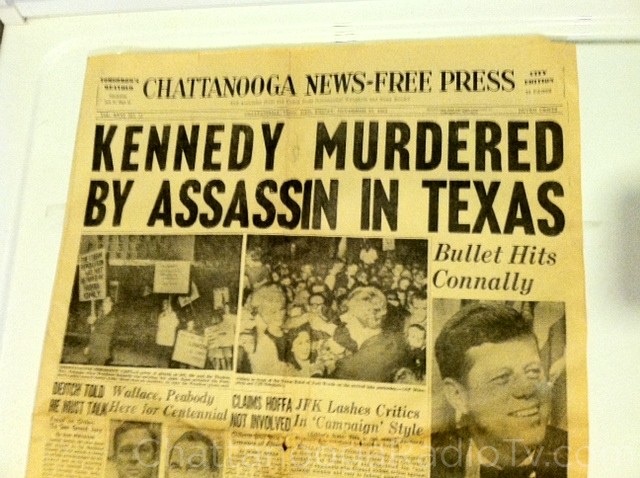

When the news reached the Chattanooga News-Free Press newsroom, the final edition of the afternoon paper was already rolling off the presses. Reporter J. B. Collins said there were two daily editions. The “Home Edition” had a mid-morning deadline, and was on the road for delivery throughout the region by early afternoon. The “City Edition” deadline was 12 noon. It allowed for coverage of late-breaking morning stories and was primarily sold and delivered within the city limits. Collins says that when the JFK news broke, there was only a skeleton staff in the newsroom. “Most everybody had gone home, the papers were done.” But editor Lee Anderson was still on the job, and brought the presses to a halt so the front page could be updated. By 4:00, the tragic event that had occurred just a few hours earlier was in the paper on the streets of Chattanooga. The only flaw: UPI had been given an advance copy of the speech the president was scheduled to give in Dallas that afternoon. Under the headline “JFK Lashes Critics in ‘Campaign’ Style,” a story was written, and published as if the speech had actually been delivered that day. The wire services and other news organizations learned from that embarrassing mistake.

Radio personalities all over the local dial were stunned. At WDXB, deejay Jerry Lingerfelt thought his newsman Lloyd Payne was kidding at first. “We were always messing with each other, I thought he was pulling my leg until I saw the look on his face. We were all in shock. Tears were rolling down Lloyd’s face and mine too.” Earl Freudenberg had just turned 16, and was called in to answer the phones at WAPO. “I was just a part-timer, but they needed help. People were calling, wanting to know what happened, and when the funeral would be held. We started playing a lot of Mahalia Jackson’s gospel records. She had sung at the president’s inaugural ball, and she was his favorite.” On Monday morning, the day of the president’s funeral, WDEF’s top-rated Luther Masingill shelved all the lucrative commercials, and let listeners call in and pay their respects. “We couldn’t get them all on the air, but we had a lot of them. And they sure loved him.”

Fifty years after being unable to finish his air shift, Tommy Jett sums up his feelings of that day by saying, “I just remember thinking, this has to be a mistake. And to this day, I wish it was.”

I was only 7, so my memories are sketchy. But, I do remember watching the funeral on TV and I think I remember a horse-drawn hearse with giant spoked wheels? I know everyone was glued to the television.

Thanks David… I was 16 and at school that day. I have always wanted to read everything about this…watch video, etc. I have ordered the new book that has just come out.

Hi David… I was 16 and at school in Atlanta that day. I have read and watched everything I could about this ever since. I can still hear the drums as Kennedy’s body was wheeled down that long stretch of road with family members walking along.

Good job David. I was 9 years old and playing on the ballfield at school and they called us all in. There was a tv in the center of the classroom and we watched until time to catch the bus. Very sad day.

One of my first memories is of watching a black and white television and there was nothing but a sea of people – I’m pretty sure it was JFK’s funeral.

Thanks for the film… I was a Junior at Henry W. Grady High School in Atlanta. I was at school when we heard the news. Everyone was upset … and in disbelief that someone had killed JFK. As I got older… I was still interested in what they could find out about what happened. Not sure we will ever really know or believe what we are told totally.

This was such a sad time for our country – we all loved President Kennedy. He was our hope for the future.

I was in school when we were informed that Kennedy had been shot. I was allowed to leave school and go to the station (WBTS) where I remained until sign off at sundown. When the President passed away the UPI teletype started ringing and wouldn’t quit. It was the first and only time I ever took a FLASH off the UPI machine. It’s like it was yesterday!