I can’t tell you how many times people have said, “Why don’t you share some stories of your early, wacky days as a teenage disc jockey? I can’t tell you, because that hasn’t happened. But if it had, I’d start with this one:

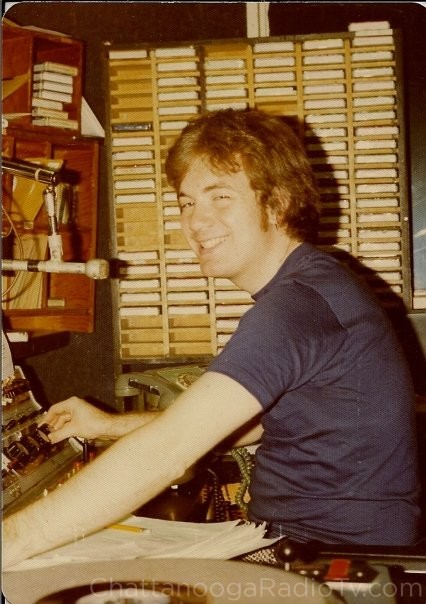

At the ripe age of 19, I was doing the afternoon show at WFLI in Chattanooga. I had been the weekend DJ at WEPG in South Pittsburg during my teen years, and had perfected the art of doing the “transmitter meter readings” far in advance. According to that important-looking paper on the clipboard, the FCC required hourly meter readings. But, since the scary old FCC inspector had not yet paid me a visit, I didn’t worry about it. I would take a quick glance at the meters early in my four-hour shift, and write down all the numbers in advance so I wouldn’t be bothered with it again. I could then get back to the serious business of playing K.C. and the Sunshine Band songs, and talking to girls on the phone.

Besides, I didn’t know what those numbers meant anyway. Back then, a deejay could pursue either of two types of FCC radio licenses. A first-class license was for smart guys, the engineers. They usually had to go to school and take special courses in order to pass the test. The lesser third-class license required memorization (or cramming) of facts and figures that were easily learned, and quickly forgotten. Passing that test enabled teenagers who had never changed a light bulb to suddenly take control of a radio station. Meet Mr. Third-Class.

I didn’t like to spend a lot of time near the transmitter. It was a monstrous, scary contraption with ominous red buttons, giant switches that looked like they could shut power off to the entire city, and “Caution!” signs everywhere. Each day, depending on the time of day I was working, I had to increase, or lower the power from 50,000 watts to 1,000 watts. I had no qualifications or interest for this task. I merely followed the step-by-step directions each day, and hoped for the best. I would know I had raised the power correctly when the folks who lived the near the station in Tiftonia would call to complain that they were hearing us on their toaster, their bedsprings, their telephones and their tooth fillings.

I didn’t like to spend a lot of time near the transmitter. It was a monstrous, scary contraption with ominous red buttons, giant switches that looked like they could shut power off to the entire city, and “Caution!” signs everywhere. Each day, depending on the time of day I was working, I had to increase, or lower the power from 50,000 watts to 1,000 watts. I had no qualifications or interest for this task. I merely followed the step-by-step directions each day, and hoped for the best. I would know I had raised the power correctly when the folks who lived the near the station in Tiftonia would call to complain that they were hearing us on their toaster, their bedsprings, their telephones and their tooth fillings.

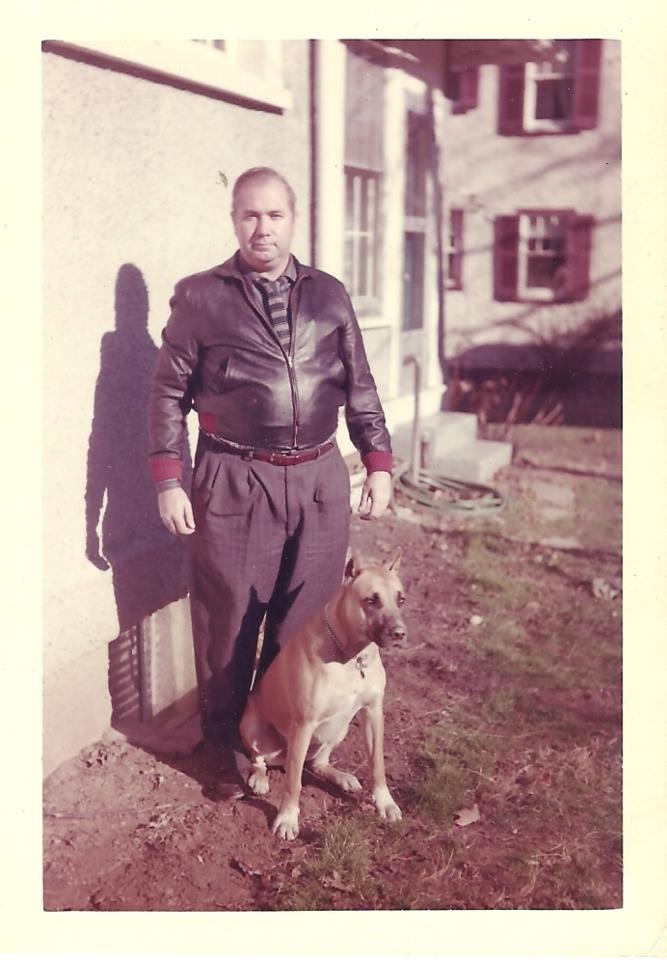

One fine afternoon, I started my shift at 2:00, took that long, 10-second stroll over to the read the meters, and wrote ‘em down for 3:00, 4:00, 5:00 and 6:00. As usual, I varied the numbers a bit, so that it looked like the 4:00 readings were slightly different from the 3:00 readings, and so on. That way, if anyone ever really looked at those numbers a day or two later, they’d think I had actually been doing my job in a competent manner. At about 2:55, the station owner, Billy Benns paid a rare visit to the control room, accompanied by his companion, a large dog named King. It was a Friday, and Mr. Benns, who was known to be somewhat cranky, was especially irritated on Fridays when he had to sign all those paychecks. Mr. Benns, who had assembled that transmitter piece by piece when he put WFLI on the air 15 years earlier, was an engineering genius. Among the deejays, Mr. Benns was respected, and feared. Mostly feared.

He put on his glasses, found the clipboard and looked at the transmitter log, studying it intensely. I tried to stay cool, tapping my feet and swaying to the beat of “Rock the Boat.” But I knew I was busted. He put down the clipboard and said, “Uh…Mr. Carroll.” (He addressed all of us kid deejays formally, which I found very flattering.) “Do you have a crystal ball? Can you predict the future?”

Using my well-honed ad-libbing skills, I mumbled, “Uh, sir, well I uh, you know, it’s funny you should ask…” Before I could continue sputtering, he asked, “How do you know what the meters will read at 4:00? At 5:00? That’s several hours from now, Mr. Carroll!” I’m sure I had a really clever comeback all ready to go, but he continued.

“You know the FCC could shut us down for this, right Mr. Carroll? And you, sir, would be out of a job. Now don’t let this happen again.” I was about to pledge my newly found devotion to hourly meter readings when he grabbed the door, turned around and said, “And start playing more Elvis! Let’s go, King.”

“Yes sir, Mr. Benns.” He walked out, and I cued up “Burning Love.”

like this love elvis keep this up.